“My policy is to have no policy.”

Abraham Lincoln (1809 – 1865)

Surprisingly often, what weighs us down are those unnecessary attachments we have to the past.

Usually, comes in the form of repeating the same tired formulas which may have worked in the past.

But now they only serve to hold us back.

Instead, you should be ruthless with yourself; stop repeating the same old methods and try to unlock your creativity by thinking of newer and better ways of doing things.

Perhaps this might even entail having to force yourself to strike out in a new direction, despite all the risks involved.

But at the end of the day, despite how hard it may seem, that is how you grow.

What you may lose in comfort and security, you gain in surprise, thus making it harder for your enemies to tell what you might do next.

Thus, you should wage war on your mind; root out all those tendencies that make you static and stale as a strategist, and embrace a more fluid and mobile state of mind.

But first, a story…

Prussian Inflexibility Vs. Napoleon’s Creativity

“When in 1806 the Prussian generals… plunged into the open jaws of disaster by using Frederick the Great’s oblique formation, it was not just the case of a style that had outlived its usefulness but the most extreme poverty of imagination to which routine has ever lived. The result was that the Prussian army under Hohenlohe was ruined more completely than any army has ever been ruined on the battlefield.”

Carl von Clausewitz, On War (1780-1831)

There are not many who have risen to power as quickly as Napoleon.

In 1793, he went from captain of the French Revolutionary Army to brigadier general in a single year.

He was just 24 years old.

In 1796, he led the French army in the Italian campaign against the Austrians, whom he went on to emphatically defeat.

By 1801, he was First Consul of France, and emperor by 1804.

Napoleon, astonishingly, had forged an empire at just 35 years old.

For many he was, and still is seen as a genius of warfare, and perhaps the best general that ever lived.

However, this assessment was not agreed upon by everyone.

First amongst these dissenters were the Prussian generals who put his success down to mere luck and fortune.

Wherever he happened to be aggressive and rash, his opponents happened to be weak and timid.

Should he fight the Prussians, he would be exposed as the hoax that he is.

Perhaps first amongst these Prussian generals was a certain Friedrich Ludwig of the illustrious Hohenlohe military family.

When he began his career as a young man, he had served under Frederick the Great, the Prussian king who had virtually single-handedly fashioned Prussia into a force to be reckoned with.

Hohenlohe would later rise through the ranks and become general at fifty – quite young by Prussian standards.

For Hohenlohe, warfare was a matter of organization, discipline, and superior strategies developed by minds well accustomed to the military arts.

The Prussians exemplified this thinking.

Their soldiers relentlessly trained until they could perform elaborate maneuvers like clockwork.

Compared to them, Napoleon was a mere hothead leading an unruly army.

So, by using their all-encompassing superiority, they would out-strategize, out-maneuver, and out-everything him.

They would reign supreme, and the French would be left utterly destroyed.

Thankfully, in 1806, they finally got what they wanted.

The Prussian king notified them that in six weeks he would declare war on the French – after a string of broken promises, Napoleon had left him no other choice.

Within six weeks, his generals were expected to come up with a plan to overcome the French emperor.

Unsurprisingly, Hohenlohe was overjoyed – this campaign would become the highlight of his career.

For years he had been thinking about the best way to beat Napoleon, and so he presented his grand strategy at the next planning session with his fellow generals.

The following was his plan: he would, using very precise marches, place the army at the perfect angle from which to attack the oncoming French army.

Then an attack using Frederick the Great’s oblique formation would devastate Napoleon’s army.

The other generals, now in their sixties and seventies, presented their own plans as well.

However, they were also merely variants of the sort of tactics Frederick the Great had used once upon a time.

Soon the discussion became an argument, an argument which went on for weeks until the king was forced to step in and create a compromise strategy.

And so, as the clock slowly ticked in anticipation of the king’s declaration of war, a feeling of exuberance started filling the country at the prospect of once again reliving the glory days of Frederick the Great.

Napoleon had excellent spies – and so knew of all their plans.

But that didn’t faze the Prussians.

Why?

Because once the Prussian war machine got moving, there was nothing that could stop it.

A few days before the king was to declare war, disturbing news came to the Prussians.

Shockingly, the French were already massing deep in southern Prussia, which totally caught the Prussians off guard.

So how did they get there so quickly?

It turns out that the French were carrying their supplies on their backs, which granted them frightening levels of speed and mobility.

The Prussians, on the other hand, were still using slow-moving wagons to transport their goods.

But before the generals even had the chance to change their plans, Napoleon suddenly made a beeline for the Prussian capital, Berlin.

Panic set in.

The generals argued and dithered, then started sending their troops hither and thither.

They had no idea what to do.

Finally, the king ordered a retreat – he wanted his troops to reassemble in the North, and attack Napoleon’s flank as he moved towards Berlin.

Hohenlohe was put in charge of the rear guard, to make sure that the Prussians were not attacked from behind.

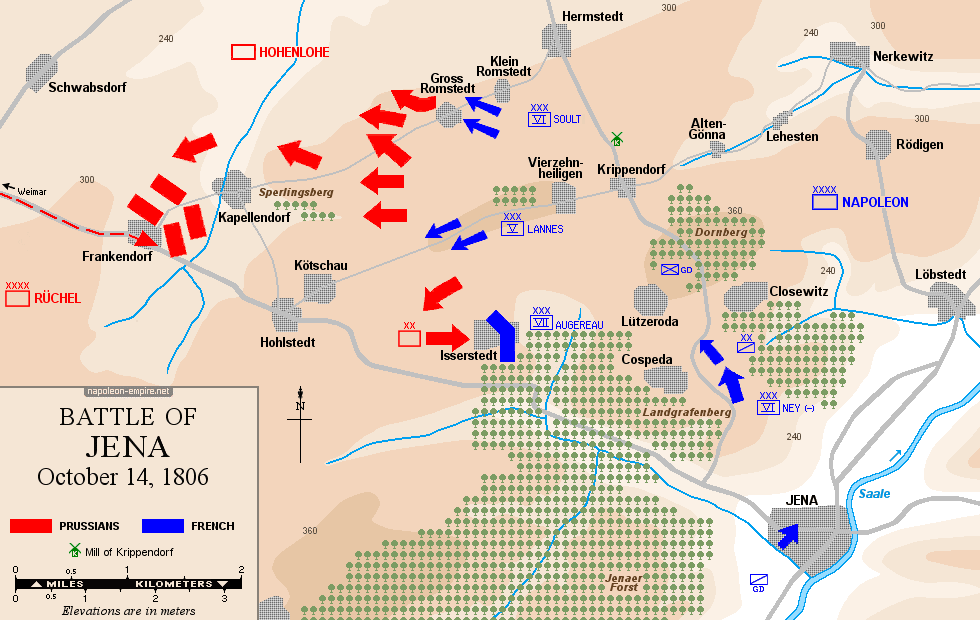

On October 14 1806, Napoleon finally caught up to the Prussians near the town of Jena.

Since he was at the back, it was Hohenlohe who was given the task of dealing with the French emperor.

Finally, he had been given the battle he had so desperately wanted.

Both sides were equal in number; but whilst the French were a seemingly uncontrollable bunch, running here and there without any discernible order, Hohenlohe kept his army in tight order, conducting them like an orchestra.

The fighting went on until the French gained the upper hand with the capturing of Vierzehnheilgen.

Hohenlohe ordered his troops to retake the village.

The Prussians, you see, in a tradition dating to Frederick the Great, controlled their army through the use of drums.

A drum would be beaten, and the army would move in perfect order.

This normally worked well, but in this case, the Prussians were in an open plain which made them very exposed.

To exploit this, Napoleon simply put shooters on top of the houses and buildings, who then began felling the Prussians one by one.

It was quite a spectacle.

The drum would be beaten, the Prussians would maneuver in perfect unison, and the French would continue sniping and annihilating the Prussian line.

Never had Hohenlohe seen any such thing before.

These French soldiers were unbelievable.

Unlike his disciplined soldiers, they moved on their own like madmen, yet there was still a method to their madness.

This continued for a while, until the moment was ripe, at which point the French suddenly surged forward and were just about to surround the Prussians.

To prevent this Hohenlohe called a retreat, and the Battle of Jena was over.

On hearing the news, the king fled east, and in a matter of days, the Prussian army fell like a house of cards after a string of stinging defeats.

Analysis

The matter facing the Prussians was simple – they had fallen behind the times.

Their generals were old and had long succumbed to a conservative mindset after losing the dynamism and flexibility they had once possessed in their youth.

This saw them repeating the same old tactics and formulas that had once worked in the past.

The army moved slowly, and the military establishment had fallen prey to a predator that had felled many in the past – arrogance.

But they certainly had many signs warning of impending disaster.

Several young officers had preached reform.

And they even had a whole 10 years to study Napoleon and his speed, his flexibility, along with his innovative strategies.

Reality was staring them in the face, and so did they face it?

No, they simply ignored it.

Instead, they comforted themselves with the naïve thought that it was in fact Napoleon who was doomed.

The fate of the Prussian army may just seem like an interesting historical anecdote, but perhaps you are moving in the same direction as well.

The same thing that limits nations and armies also limits individuals – the inability to see things for what they are.

As we grow in age, we become more and more rooted in the good old days.

That which might have worked in the past becomes dogma, so we fall to those same methods time after time again.

Repetition, you see, comes at the expense of creativity.

Doing one thing every single time robs you of the opportunity to experiment with other things that might work even better.

Yet, we don’t see that what we are doing prevents this.

So, when a young Napoleon comes along, who respects no tradition, and fights in a whole new way, only then do we realize the error of our ways.

But who knows? Perhaps by then, it’s much too late.

Never take for granted your past victories.

Those past wins may in fact be a stumbling block for you.

Every war and every battle is different.

Every new day is different, and so is every new year.

If you fight this new battle like you did in your last battle, this may in fact become your final battle.

Miyamoto Musashi’s Method

“Thus, one’s victories in battle cannot be repeated – they take their form in response to inexhaustibly changing circumstances.”

Sun Tzu, Art of War (sixth century B.C.)

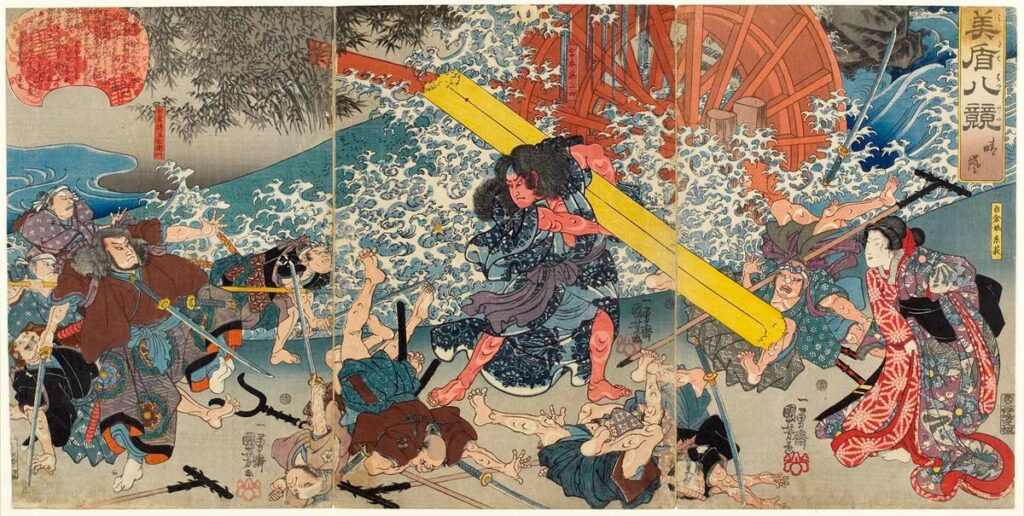

Miyamoto Musashi, the famous Japanese samurai, was challenged to a duel in 1605.

By then he had already made a name for himself as a paragon amongst swordfighters, but here, he was challenged by a member of the renowned Yoshioka family.

Already he had defeated and killed two members of their family – thus they were thirsting for revenge.

However, Musashi smelled a trap.

Yet, despite his friends offering to accompany him to make sure nothing foul happened, he still decided to go alone.

In his previous fights against the Yoshioka’s, he had infuriated them by arriving late.

By getting into their heads, he had given himself an advantage which he used to win the fights.

But this time, he decided to do something different.

Instead, this time around he chose to come early and hid behind the trees.

What he saw next was very interesting.

Thinking he would come late once again; the Yoshioka men came to the meeting place and laid an ambush for Musashi.

But their plan was doomed to fail.

Musashi jumped out of his hiding place and cut down the dazed Yoshioka men one after another.

This astonishing victory would seal his reputation as one of Japan’s greatest swordsmen.

Later, as he roamed the country looking for suitable challengers, Musashi learned of an undefeated warrior named Baiken who had defeated his challengers with a sickle and long chain with a steel ball attached to it.

Wanting to experience his technique, he met Baiken, and soon a duel was set.

Like before, Musashi’s friends were unsure about this duel – Baiken was unbeatable.

Baiken, you see, had a unique technique.

He would rush at his opponent, then throw the chain with the ball at his opponent’s face.

His opponent would have to shield his face from the attack, but during that split second Baiken would cut him down with the sickle.

Yet, even whilst knowing this, Musashi didn’t let his friends deter him.

Instead, he chose to bring two swords this time – one short sword and one long sword.

When Baiken saw this, he was perplexed.

He had never fought someone using two swords.

The duel started, and instead of letting Baiken rush at him, Musashi charged at him first.

Baiken hesitated to throw the ball and instead retreated a little.

Suddenly Musashi knocked him off balance with a blow from the short sword, then stabbed him with the long sword.

Just like that the undefeated Baiken was killed.

Analysis

The reason Miyamoto Musashi won all his engagements was this: he adapted all his strategies to his opponents and the circumstances of the situation.

When the Yoshioka expected him to come late, he came early.

And with Baiken, it was simply a matter of bringing two swords instead of one, and rushing at him before Baiken had the chance to do so.

Musashi’s opponents depended on flashy techniques and unorthodox weaponry.

But that is the same as fighting the same battle as last time.

Rather than adapting to the situation, they relied on the same technology or techniques that worked last time.

And so, much like Napoleon, Musashi used their rigidity against them.

Unlike them, he anchored himself in the moment.

He thought of ways of surprising and unbalancing this particular opponent.

Then he thought of a way to turn his newfound advantage into victory.

From a very young age, Musashi had learned that the essence of strategy was in adapting his methods to each situation as they arrived.

To use his creativity, in other words.

Strategy is not a question of who has learned the most moves or techniques.

Nor is it a recipe book that can be followed in a step-by-step fashion.

There is no magic formula for success.

Techniques, technology, and theories merely give you more ways of winning.

They exist so that in the heat of the moment they might inspire a new direction for victory.

Learn to not rely on these things, rather learn to rely on your own creativity.

Such is the Way of the true strategist.

Change Your Thinking

After a defeat or an unpleasant experience, we often find ourselves thinking that if only we had done this, or if only we had done that, then everything would have gone our way.

Many a general, after suffering an excruciatingly painful defeat, had gone through this thinking process.

Even Hohenlohe, years later, could see how he might have stopped Napoleon.

But the problem, you see, is not that we figure out what the problem is only when it is too late.

The real problem is that we think that it is knowledge we are missing, that if only we had known more, then the outcome would have been different.

But that is precisely the wrong approach.

What makes us go down the wrong path in the first place is that we are unattuned to the present, we are insensitive to the circumstances presenting themselves before us.

Instead, we are in our own little bubble.

We are reacting to events that happened in the past.

We are applying theories and ideas that have little to do with the situation we are in right now.

More books, theories, and useless thinking only make the issue bigger.

The most successful generals, the most creative strategists stand out not because they have the most knowledge, but because they are able to drop their preconceived ideas and instead focus solely on the present moment.

That is how creativity is sparked and an opportunity is grasped.

Knowledge, experience, and theories have their limitations.

There is always going to be something we do not know.

Therefore no amount of useless thinking can prepare us for the constant flux of everyday life.

The military philosopher von Clausewitz calls this ‘friction’: the difference between what we think will happen and what actually happens.

Since this ‘friction’ is inevitable, we must keep our minds flexible enough and adaptable enough to deal with each new situation presenting itself.

The better we adapt our actions to the situation, the more realistic our responses will be.

Alternatively, the more we lose ourselves in the past, or in books and theories, the more inappropriate our responses become.

But this is not to say it is wrong to analyze our past mistakes.

The point is that by developing the capacity to think in the moment, we will make fewer mistakes, and thus we will have less to analyze.

Think of the mind as a constantly moving river.

When it is healthy, it moves forward and responds to each twist and turn as it presents itself.

But when there are too many preconceived notions, and too many thoughts of the past, these act like boulders that block the path of the river.

The river stops moving, and stagnation sets it.

You must stop this tendency of the mind.

First, you must become aware of this tendency, and second, you must fight it.

Sometimes Education is the Problem

When Napoleon was asked what principles he followed, he answered none.

His genius was to respond to each situation as it came and to make the most of what he was given.

He was, therefore, the supreme opportunist through and through.

Thinking that strategy is about timeless rules, and formulas will be your undoing.

Take a page from Napoleon’s book; the only principle you should have is to have no principles.

Studying his tactics and strategy can certainly broaden your vision of the world, but you must combat the tendency to convert theories into doctrine.

Be brutal with the past, and with old ways of doing things.

Often the problem is our education itself.

During WWII, the British, who were well-educated in tank warfare were fighting the Germans in the deserts of North Africa.

Yet, later in the campaign they were joined by the Americans who were less educated in these tactics.

Soon though, as they adapted to the situation in front of them, they were fighting in a way superior to the methods the British were using.

The leader of the German army in North Africa, Erwin Rommel, commented that the “Americans… profited far more than the British from their experience in Africa, thus confirming the axiom that education is easier than re-education.”

What he meant was that education has the tendency to burn ideas into our minds, ideas that are harder to shake.

When a chaotic experience occurs, like on a battlefield, the trained mind will often fall back on learned rules and experiences rather than on the changing circumstances.

When faced with a new situation, sometimes it is best to imagine you know nothing and that you need to start learning all over again.

Clearing your mind of all you thought you knew will give you the space to be educated by the best school of all, the present situation.

This will allow you to develop the strategic muscles needed rather than depend on someone else’s books and theories.

Forget the Last Battle

The last battle you fight is always a problem.

And that is regardless of whether you win or lose.

If you win, you might be inclined to become lazy and complacent, which will cause you to rely on strategies that have no place in your current engagement.

On the other hand, a loss will make you indecisive and fearful of failure.

You must, therefore, erase your memory of your last battle at all costs.

The skillful North Vietnamese general Vo Nguyen Giap, after a successful campaign made a point of telling himself he was in fact a failure.

This allowed him to never become drunk on his success, whilst also allowing him to have the presence of mind to understand and correct the mistakes he might have made even when he did well.

But most importantly, this allowed him to never repeat the same strategies in the next battle.

Rather he had to think through this new situation anew.

Just Keep Moving

When we were children, our minds never stopped.

We were open to new experiences and absorbed as many of them as possible.

When we became frustrated or upset, we would find a creative way to solve our problem.

And we would do this as we crossed paths with each new situation.

All the great strategists were childlike in this respect, whether this was Napoleon, Zhuge Liang, or even Miyamoto Musashi.

The reason is simple: the true strategist sees things as they are.

Nothing stays the same in life, everything is in flux.

Thus, it takes a great amount of mental fluidity to be able to keep up with each circumstance as it changes.

Their minds were always moving and were always excited and curious.

They quickly forgot the past- for the present was much too interesting.

That is why they were so highly sensitive to dangers and opportunities.

The famous Greek philosopher Aristotle thought that life was defined by movement.

That which did not move had no life, that which did not move was dead.

As children, our minds were full of movement, in much the same way as Napoleon’s.

But as we grow older, our minds become less mobile, and we become like the Prussians.

Often, we look to recapture our youth through our looks, or fitness.

But true youthfulness is characterized by a mobile and fluid mind.

Whenever you find yourself uselessly thinking too much about an obsession or resentment, push yourself past it.

Distract yourself with something else.

Like a child, let yourself be absorbed by something else entirely, something more worthy of your concentrated attention.

Don’t waste time on things you cannot change or influence – just keep moving.

Constantly Change, Constantly Adapt

Throughout history, there have been epic confrontations between the past and present.

This happened in the seventh century, the armies of the Muslims used a new form of desert fighting to totally conquer the Persian empire and carve out a huge portion of the Byzantine empire.

It also happened in the thirteenth century when the Mongols used seemingly limitless mobility to overwhelm the comparatively heavy armies of the Russians and the Europeans.

Or even at Jena when the static Prussians were overcome by the youthful and dynamic French army.

In each case, each conquering army was at the cutting edge of their discipline by creatively developing new fighting forms.

You can reproduce this on a smaller scale by attuning yourself to the trends which have not yet fully taken hold, and by capturing the spirit of the times.

As time passes, change up your style to something new, something fresher, something better.

This was how Netflix pushed Blockbuster out of business.

Whilst Blockbuster held onto the old ways of in-store video rentals, Netflix leveraged the internet to offer the cutting-edge technology of video streaming.

Instead of sentimentally being attached to an old way of doing things like Blockbuster was, constantly adapt and change your style.

This will help you avoid the pitfalls of your previous battles.

Just when people think they know you, you change – that is the hallmark of the true strategist.

Reverse Course

Sometimes you need to shake yourself awake and break away from the routines and habits that you have become accustomed to.

When you do the opposite of what you usually do, or something totally different, you are then thrust into a new situation.

And when that happens the mind snaps into focus.

The change can be alarming, but it can also be refreshing and exciting.

Even in relationships, this can happen.

You do what you usually do, and then the other person does what they usually do, and the monotonous cycle starts over.

When you reverse course and change the entire dynamic, everything becomes altered, new possibilities open up, and the excitement returns.

Wrapping Up

Try to think of yourself as a general.

A general must adapt to the complexity and chaos of modern warfare by becoming more fluid, more mobile, and more creative.

The ultimate form of this warfare is guerrilla warfare which exploits chaos and unpredictability as a strategy.

This form of warfare follows no set strategy, nor does it repeat the same tactic a second time.

The guerrilla army has no set form and is simply pure mobility.

That is the new model you should apply to your mind.

Apply no theory too rigidly, don’t let your mind become static.

Attack from new angles and adapt to the landscape and situation you are given.

By staying in constant motion, you give your enemies no set target to aim at.

And you exploit the chaos of the world rather than succumbing to it.

Such is the Way of the Strategist.

Footnotes & Further Reading

Greene, Robert. The 33 Strategies of War. Millionaire