The approaching Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) was to be the final of the Anglo-French wars between 1689 and 1815, and this time, it would last a remarkable twelve years.

Not only would it be the last, but it would also be the most testing and bloodiest of them all.

By the time the French Revolutionary Wars had concluded, the French had conquered large swaths of European territory, and Napoleon had crowned himself emperor.

Check out our Prelude to the Napoleonic Wars for about that.

But Britain, along with the now-conquered satellite states were still thirsting for retribution and revenge.

Overview of Strengths and Weaknesses

Just as before, each combatant (Britain and France) had its own strengths and weaknesses.

Despite some difficulties, Britain’s Royal Navy was at this time in a very strong position.

While powerful squadrons blockaded the French coast and captured its colonies, those of its satellites were systematically captured by the Royal Navy as well.

From Tobago to Java, and from Senegal to India, foreign colonies continued falling into Britain’s hands at the expense of the French.

Although it did not have a direct impact on the goings on in Europe per se, it certainly allowed Britain new markets to send their goods after Napoleon had blocked British goods from being sent to the European states he controlled (which was, safe to say, was almost all of them by 1808).

Nevertheless, the Royal Navy was still in enough of a dominating position for the French to start considering more seriously an invasion of southern England to combat this threat.

And by then, with Napoleon’s Grande Armée having been assembled and William Pitt the Younger having been returned to office in 1804 as British Prime Minister, each side grimly looked forward to the final, decisive clash.

What would quickly become obvious between 1805 and 1808 was that despite containing several famous battles, the same strategical constraints that had plagued both sides in the past did so again.

Indeed, although Napoleon had an army three times larger than the British, he first needed command of the sea before he could even think about safely landing in England.

Numerically speaking, France had a considerable navy (about seventy ships), and it was bolstered by the Spanish who joined the war in 1804 (twenty ships).

Yet the Franco-Spanish ships were scattered over many areas, and they could not run the risk of falling prey to the Royal Navy which possessed vastly greater battle experience.

And when they were exposed to its superior battle experience, they would both be crushed as happened at the hands of Lord Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805,

In this single engagement, the gap in quality was made evident in the most humiliating way.

Nonetheless, despite that victory securing the British Isles, it could not undermine Napoleon’s position on land.

And it was for this reason that Pitt was willing to tempt Russia and Austria into a Third Coalition, paying £1.75 million for every 100,000 men that they put on the field.

But even before Trafalgar happened, Napoleon had already rushed his army from Boulogne to the Upper Danube, where he wiped out the Austrians at Ulm, then proceeded to smash an Austro-Russian army of 85,000 men at Austerlitz in December of that year.

As a result, for the third time, Austria sued for peace, which allowed the French to assert greater control in the Italian peninsula, and thus compel a hasty withdrawal of the Anglo-Russian forces there as well.

These defeats only signaled just how difficult it would be to take down a military genius like Napoleon.

As a result of these victories, the following years would usher in the zenith of French predominance.

But there was still some resistance.

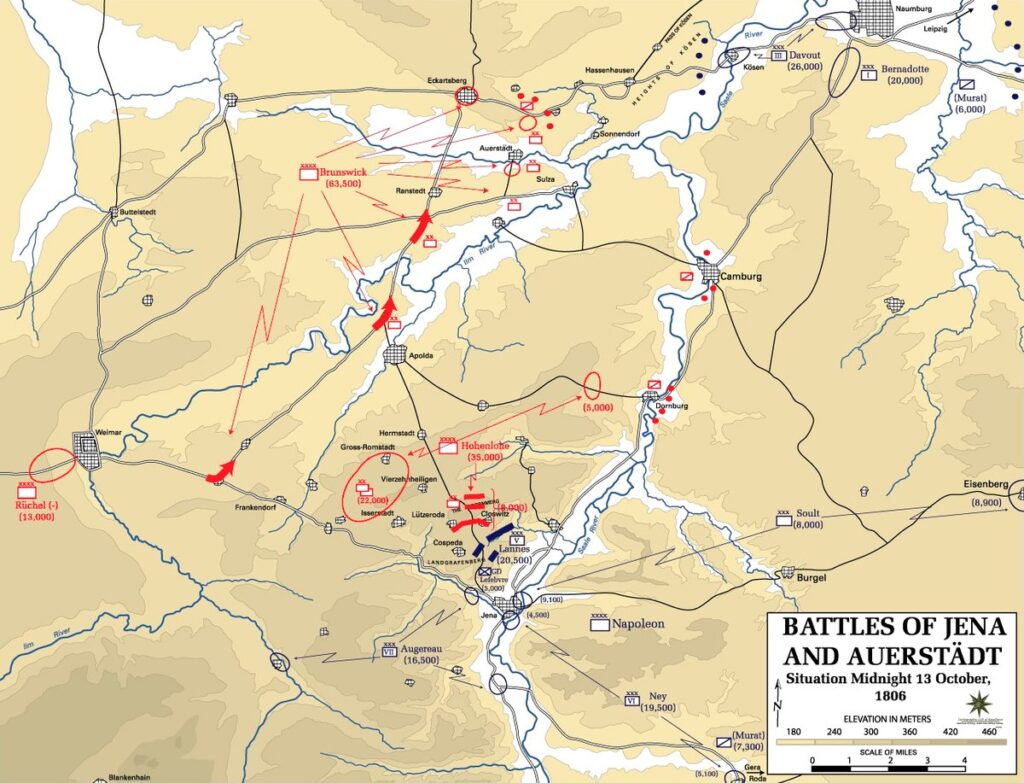

Prussia, who had earlier abstained from the Second Coalition, rashly declared war in October 1806; as with Austria before them, they were promptly defeated in the same month at Jena.

Russia too, although much more stubborn, was badly hurt at Friedland in 1807.

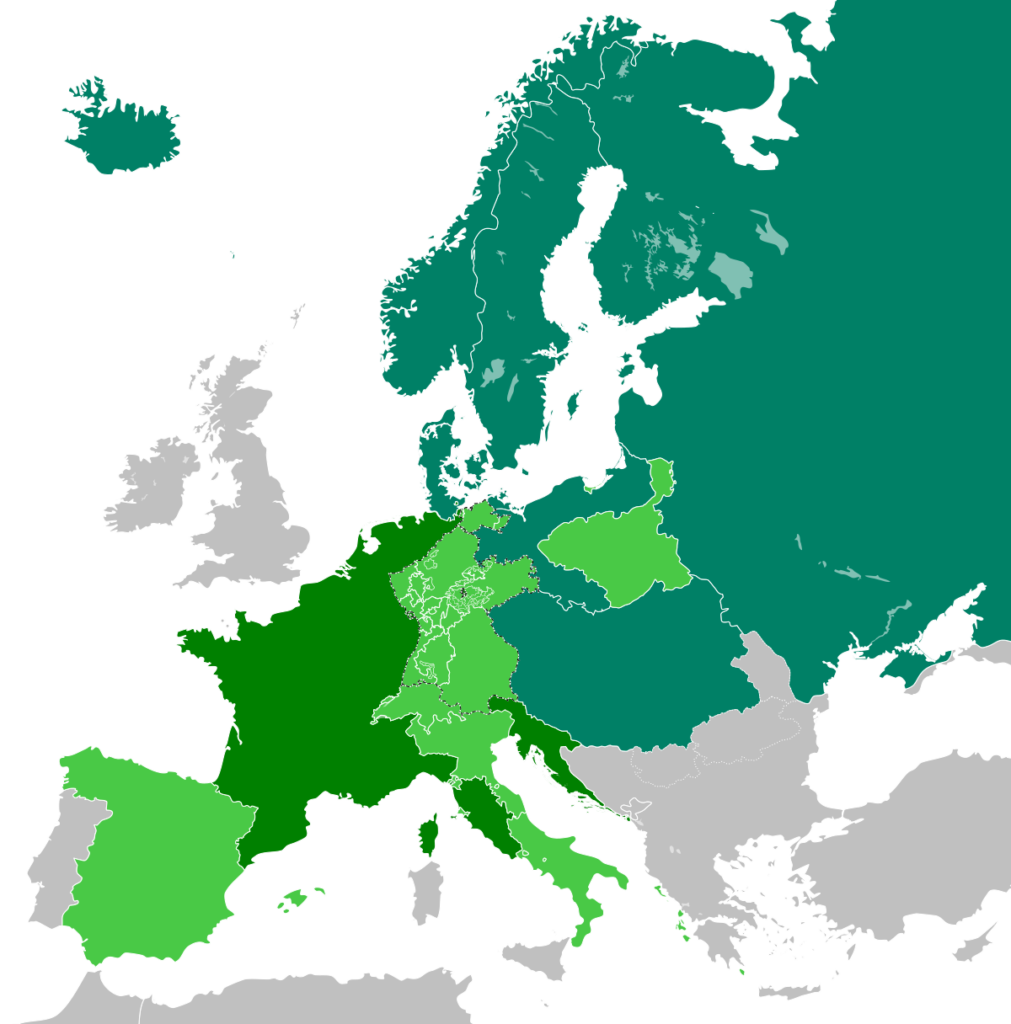

At the Tilsit peace treaties, Prussia would become a satellite of France, while the Russians escaped lightly.

But they too were forced to ban British trade and promise to join a French alliance.

Elsewhere, the German states were merged into the Confederation of the Rhine, and western Poland became the Dutchy of Warsaw.

Spain, Italy, and the Low Countries were made subservient, and the Holy Roman Empire was ended by Napoleon after one thousand years of existence.

Hence, by the end of 1808, between Portugal and Sweden, there existed no independent state, and thus no ally for the British.

And Napoleon would exploit this small window of opportunity to weaken the British indirectly before a further direct assault occurred – by targeting its economy.

The Economics of the War

He prevented European shipbuilding resources needed for the Royal Navy from reaching Britain, and given Britain’s dependence on European markets for exports, the was immense.

What this meant was that the reduced earnings from exports would deny London the monies needed to subsidize any ally in Europe or purchase the necessary goods necessary to field its own expeditionary force.

Much more so than ever before, military strategy and economics were becoming more and more intimately linked.

So, with each seeking to ruin the other in so many spheres, the relative merits of their two economies deserve analysis.

The State of the British Economy

There is no doubt that Britain’s unusually large reliance on exports made it particularly susceptible to the trade bans imposed under Napoleon’s ‘Continental System’.

In 1808, and again in 1811-12, this led to vast stocks of manufactured goods piling up in docks across England due to the loss of European buyers.

This led to unemployment, and unrest, as well as a staggering increase in the national debt.

To make things worse, after relations with the US became strained, exports to that important market tumbled and continued to exert economic pressure.

And yet, the problems ended up subsiding, chiefly because they were never applied long or consistently enough.

When revolution in Spain occurred against French hegemony in 1808, Britain’s economic pressure was relieved, and this happened again when Russia broke with Napoleon’s trade embargo, thus relieving Britain again in the 1811-12 slump.

Still, it turns out that throughout this period goods were being smuggled throughout Europe.

When the official channels of exports were shut, Britain bribed port officials to get their goods to eager European customers, in much the same way they did during the War of 1812 against the US when goods were smuggled through Canada to New England.

Finally, British export trade could also be sustained by regions unaffected by the Napoleonic ‘Continental System’ or the American ‘nonintercourse’ policy.

Asia, Africa, the West Indies, Latin America (despite Spain’s best efforts) and the Near East all grew in importance during this time.

So although in some markets for some time British trade was restricted, Britain’s overall exports increased from £21.7 million (1794-6) to £44.4 million (1814-16) – a truly astonishing growth indeed.

The other main reason why the British economy did not nosedive during this period was that unfortunately for France, Britain was well into the Industrial Revolution.

This meant that huge government spending aimed at producing armaments saved the important iron, steel, coal, and timber industries, among others.

This fact, along with the introduction of new export markets to British goods boosted the economy as the French blockade tried to depress it.

A vast new array of docks and new canals that came with the fall of its enemies’ colonies further easy access to transportation and necessary raw materials.

And regardless of whether this ‘boom’ would have occurred had this war happened or not, what is clear is that British productivity and wealth were rising fast.

The economy would continue to grow fast, and taxes collected by the government would reach the staggering figure of £1.217 billion.

Additionally, the British government was able to raise a further £400 million in loans from the financial markets – much to Napoleon’s dismay.

In the critical last few years of the war, they were still raising an extra £25 million a year in order to give themselves that extra advantage, and this permitted them to endure the rising costs of the wars better than France.

The Napoleonic Economy

The story of France’s economy during the Napoleonic wars is an even more complicated one for historians to unravel.

The outbreak of the French Revolution certainly did see a contraction of the economy for a while.

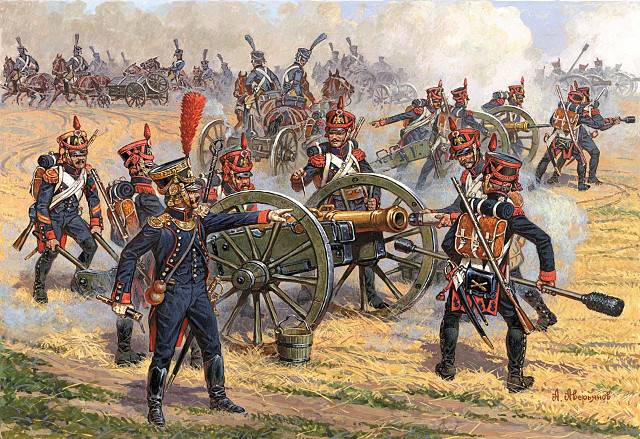

Yet soon, the outpouring of public support and the mobilizing of national resources saw an astronomical increase in the production of small arms, cannons, and other military equipment, which in turn boosted adjacent industries such as iron and textiles.

Moreover, Napoleon’s legal and administrative reforms would sweep aside many of the economic obstacles that were present during the old order and thus aid modernization, which France was sorely in need of.

This in turn interacted with a population increase as well as the introduction of new technologies which helped increase prosperity.

In any case, however, France’s growth was still slower than that of Britain.

And the chief reason for this was that the agricultural sector during this period saw very little changes in productivity.

Poor communications continued to prevent farmers from accessing the national market and instead had to be satisfied with being limited to their local markets, while there was a general lack of encouragement for radical innovation which would make production more efficient.

This conservative mindset also impeded its industrial sector which failed to take up new machinery and innovative technologies as quickly as the British did.

And the Continental System in general only helped the important cotton industry to the extent that it prevented inferior French cotton from competing with the vastly superior British colonially produced cotton.

On the whole, French industry actually emerged from the war distinctly less competitive because of this protection from foreign rivals.

And the loss of its foreign colonies continued to force the French economy to turn inwards.

Whilst its Atlantic sector was previously its most industrialized and the fastest growing during the seventeenth century, it was increasingly being cut off by the Royal Navy.

This led to many cities dependent on foreign trade such as Bordeaux and Nantes becoming economically crippled.

So, deindustrialized through the loss of the Atlantic sector, and cut off from the outside world, France turned inward to its peasants, its small-town commerce, and its localized, uncompetitive, and relatively small-scale industries.

It is unsurprising therefore that the impact on the French economy was less than satisfactory.

Plunder

Given its clear signs of economic conservatism, and in some cases retardation, it is all the more surprising that France managed to finance such a lengthy Great Power war.

Whilst popular mobilization can explain the early years of the French Revolutionary Wars during the 1790s, it cannot explain how the later Napoleonic Wars were financed.

After all, how can an army of 500,000, which also needed probably another 150,000 new recruits per year, be paid for in such a manner?

Military expenses had already surpassed 800 million francs per year in 1813, so normal revenues simply could not pay for such outlays.

Also, the fact that in France direct taxes were unpopular, and the fact that Napoleon claimed to be hostile to raising money from loans didn’t help (although he did end up going back on his word).

Well, you see, to a large extent, Napoleon’s exploits were paid for, simply put, through plunder.

This process had begun internally when the wealth of the ‘enemies of the revolution’ was confiscated for use by the state.

So, when France’s revolutionary armies moved into foreign lands, it was altogether natural that the foreigners should pay for the wars.

Crown and feudal properties would be confiscated, along with spoils taken from armies, museums, and treasuries.

And when French regiments were kept in a satellite territory, the satellite government was required to pay for the armies – even after their valuables had been plundered.

So ingenious was this move that not only did it cover military expenses, but it produced enormous profits for France as well.

And so effective was this policy that Nazi Germany would replicate the same practice during WWII.

Additionally, when armies were defeated, they also had to pay large indemnities as well.

When Prussia was defeated at Jena, for example, it was forced to pay 311 million francs – roughly half of the French government’s ordinary revenues!

And each time Austria was defeated, not only were they forced to cede territory as a result, but they were also told to pay a large penalty as well.

So war, to put bluntly, supported further war.

And as long as its brilliant leader remained successful, the system seemed invulnerable.

In fact, this was alluded to by Napoleon himself:

“My power depends on my glory and my glories on the victories I have won. My power will fail if I do not feed it on new glories and new victories. Conquest has made me what I am and only conquest can enable me to hold my position.”

The Situation Becomes Bleak

So, taking all this into account, how exactly could Napoleonic France be beaten and brought down?

Britain lacked the military manpower to fight on land, and a single continental opponent was always doomed to fail.

Prussia’s ill-timed entry into the war only proved this point, but that didn’t stop the frustrated Austrians from renewing hostilities once again in 1809, and whilst they put up a spirited distance in the beginning, they were once again compelled to stop fighting and cede additional lands to France.

It’s even more impressive considering that French successes against Austria came straight after Napoleon drove into Spain to crush a revolt.

So it seemed that wherever revolt did occur, it was swiftly put down by the French emperor.

And while the British showed similar ruthlessness in their naval campaigns as in the attack on Copenhagen in 1807, they still tended to waste military resources in small-scale raids in Italy an incompetent attack on Buenos Aries, and finally, the terrible Walcheren operation in 1809.

Indeed, the situation was becoming more and more hopeless for France’s enemies.

Yet, it was exactly when Napoleon seemed most unbeatable that the first cracks started to show.

The End is Near

Despite France’s successive military victories, they had come at a high cost.

At Friedland the casualties numbered 12,000; at Aspern, a whopping 44,000; at Wagram, another 30,000.

Experienced men were becoming few and far between – a third of the French army in Germany, for example, were underage conscripts.

And even though much of Napoleon’s army consisted of men from conquered territories, manpower was still becoming scarce.

This was unlike the Russians who could still draw upon huge reserves.

And even the Austrians, despite their losses, still possessed a considerable army.

These factors would become important very soon.

Further West in Spain, despite Napoleon’s best wishes, the revolt had not been fully suppressed.

By beating the Spanish national force, he simply encouraged the Spanish to adopt guerrilla warfare, which was more difficult to suppress, and multiplied the logistical issues the French were already facing.

But in fighting in Spain, and later even Portugal, Napoleon accidentally chose to fight in the few areas where the cautious British were unafraid to commit themselves.

Britain Joins the Fray

When Britain saw the success with which Wellington exploited local sympathies along with favorable geography, they began pouring resources into the conflict.

Soon their efforts started to bear fruit – during their fruitless march on Lisbon in 1810-11, the French suffered an astonishing 25,000 casualties after being defeated by Wellington’s Anglo-Portuguese army.

Not only did this highlight just how problematic ‘the Spanish ulcer’ was becoming for Napoleon (despite 300,000 troops having been dispatched there), but it also became one of the first signs of France’s impending fall.

The switch of the Spanish to its side aided the British economically as well as strategically.

For after all, for most of the duration of the Anglo-French wars, Spain had fought on the side of the French.

By allying with Spain, Britain gained market access not only in Spain itself but also in the Mediterranean and Latin America.

Although this economic relief was still overshadowed by the closure of the Baltics to British exports and the dispute with the Americans, it nonetheless greatly aided Napoleon’s foe – and it happened at just the time Europe itself was breaking into revolt.

Overstretched and Riddled with Contradictions

The eventual fall of the French Empire was due to there being a contradiction inherent in the Napoleonic system.

Whatever the merits or demerits of the French Revolution itself, it did not change the fact that a nation proclaiming liberty, fraternity, and equality was conquering non-French populations, stealing their wealth, and conscripting their youth.

This, coupled with the resentment of the conquered over the economic control of the Continental System, meant that the economic warfare Napoleon was conducting hurt its satellite states as much as it did Britain in many cases.

Yet, few could pull out as the Spanish had done, or as the Russians would do in 1810.

By the time those two revolted, others would begin to join the fray against Napoleon.

And with France fighting on so many fronts, is it surprising Napoleon’s army soon became overstretched?

However, this mode of analysis tends to obscure the personal aspects of the story, such as Napoleon’s own increasing lethargy.

It may also make it seem that Napoleon had little chance of winning once the other Great Powers had made significant enough inroads in 1813-14.

This is not true at all.

In fact, even until just before the final year of the war, France still had the resources to build a huge navy to rival that of Britain – but they did not persist in that course.

And up until the Battle of Leipzig (October 1813) which ended Frances’s presence East of the Rhine, there was still a good chance that Napoleon would smash one of the major eastern states (Prussia, Austria, or Russia) and dissolve the coalition as a result.

Yet, even before then, France’s overextension was starting to become lethal.

And as a result, a problem in one part of the system threatened to take the whole project down as it would consume such great amounts of resources.

For example, by 1811 there were some 353,000 troops in Spain, but the vast bulk of that army had to spend their efforts defending their own lines of communication rather than actually advancing against the Spanish.

And in the army that Napoleon took to attack Russia in 1812, of the 600,000, only 270,000 were Frenchmen.

This might have been fine during the successful early stages, but when troops started becoming desperate to escape the bitter Russian cold and return home after their luck ran out, this started to pose a problem.

Hence, the Grand Army’s losses during the Russia campaign were atrocious.

As many as 270,000 were killed, and 200,000 were captured.

And about 1,000 guns and 200,000 horses were lost as well.

Yet, this was only the beginning of Napoleon’s downfall, not the actual downfall (there were still two years to go).

You see, the Russians had little capacity (and little enthusiasm) to chase Napoleon across Germany after his retreat, meanwhile, Napoleon had quickly mustered a force of 145,000 men to hold the line in Saxony.

Moreover, while the other major eastern monarchies of Prussia and Austria were becoming more threatening, they were still too divided.

It was only after Wellington had defeated Joseph Bonaparte at Vitoria (thus seeing the effective end of the Peninsular War in Spain) in June 1813 and pushed the French back, that the others grew in confidence.

This victory soon gave the Austrians enough reason to combine with Russia, Sweden, and Prussia to drive Napoleon out of Germany.

Napoleon Abdicates… And Then Returns

The resultant Battle of Leipzig was unlike any other before it.

Napoleon’s army of 195,000 was overwhelmed in a matter of four days by 365,000 Allied troops.

The allied army, as usual, was underpinned by British subsidies, as well as British muskets, artillery, and other equipment.

The win at Leipzig emboldened Wellington to advance upon Bayonne and Toulouse, while Austria, Prussia, and Russia proceeded to pour into the Rhine and the Low Countries.

Although Napoleon managed to conduct a brilliant tactical defense of northeastern France in early 1814, the French populace, becoming less than enthusiastic now that the fighting was in their land, started turning against Napoleon while Britain urged the allies to keep up the pressure.

By 30 March 1814, even Napoleon’s marshals had had enough, and within another week the emperor had abdicated.

Compared to these epic events, unfortunately, the Anglo-American War of 1812 was just a strategic sideshow.

But economically speaking, had this not coincided with the fall of the Continental System, this would have been very troubling for the British.

Although each side certainly had hurt the other (the raid on Toronto by the Americans and the burning of the White House by the British serve as examples) they could not defeat each other.

In any case, apart from the resources it took from the European theatre of the fighting, it served as little more than a distraction.

This might explain why the war has little fame away from North America.

Napoleon’s final campaign in 1815 after his return from exile in Elba, while certainly important, also serves as a strategical footnote.

His return had come whilst the victors were quarreling about how post-Napoleonic Europe should be divided, but it did not break their alliance.

This is because even if he had won at the Battle of Waterloo, it is still hard to see how he may have financially sustained another long war afterward.

But it was important politically.

That battle demonstrated Prussia’s military recovery after Jena, which gave them a better bargaining position.

Moreover, it compelled all the powers to bury their differences and enshrine the principles of a balance of power in Europe.

After two decades of continuous war, the European system was at last to be fashioned along lines which ensured a rough equilibrium.

Enshrining of an Equilibrium

The final Vienna settlement of 1815 did not, as the Prussians had hoped, partition France.

Instead, it surrounded France with substantial territorial units such as the Kingdom of the Netherlands to the north, an enlarged Kingdom of Sardinia, and Prussia who were given the Rhineland.

Because of Austria’s objections, Prussia was not allowed to swallow up Savoy but rather was compensated in other areas.

Austria too was compensated with territory in southeastern Germany and in Italy.

Even Russia, who originally claimed the lion’s share of Poland, backed off after being shaken by the threat of an Anglo-French-Austrian alliance against it.

No power, it seemed would be allowed to impose its wishes on Europe as Napoleon had done.

The egoism of before was looked down upon in this subsequent period, while the tenets of the balance of power were generally accepted across Europe.

This state of affairs after the Napoleonic Wars became known as the Concert of Europe.

Rules for Thee, But Not for Me

Now, for all the talk of a balance of power, this certainly did not mean the Great Powers were of equal rank.

Whilst there was an equilibrium on land, Britain had managed to increase its near-monopoly of naval power on the sea.

Not only had it expanded in India, but it had also managed to secure overseas markets in North America, the West Indies, Latin America, and the Orient.

This not only gave it unchallenged access to new wealth abroad, but it gave Britain control of maritime routes and profitable re-export trades, as well as already being the most industrialized nation in the world.

And over the next half-century, Britain would only continue to grow and become richer, so much so it became the world’s only superpower during the 19th century.

Indeed, it seemed as though the idea of an equilibrium only applied to European territorial arrangements, and not in the colonial and commercial spheres.

Footnotes & Further Reading

Kennedy, Paul M. The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500-2000. London: William Collins, 2017.