Better one bad general than two good ones.

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821)

The problem that comes with the leadership of any group of people is that, at the end of the day, each member of the group has their own agenda.

Additionally, you must consider that if you are too authoritarian and strict, they will resent you and rebel in silent ways.

Yet, if you are too easygoing, they will forsake the group and follow their own selfish interests.

So all leaders must walk this tightrope – they cannot be too restrictive, nor can they be too permissive.

You should be careful not to let your influence overpower them, yet they should still follow you.

To do this, you must be able to delegate and put the right people in the right place.

Such people must be able to enact the spirit of your ideas without being mere robots.

Let your commands be clear and inspiring, and let not the focus be on the leader – instead, let it be on the team.

Let there be a sense of participation, but do not let your group fall into groupthink.

And as a leader, exhibit fairness and virtue, but never relinquish orderliness and effective command.

A Chain is Only as Strong as its Weakest Link

In August of 1914, WWI began.

Unfortunately for France and Britain though, by the end of that year, the two became locked into a stalemate with Germany all along the Western Front.

Meanwhile, on the Eastern Front, Germany was crushing the helpless Russians who were allied with the French and British.

So, needing a way to turn the balance against Germany, British military leaders came up with a plan that they presented to the First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill.

The plan involved attacking the Ottoman Empire (ally of Germany) via Gallipoli, a peninsula situated in the Dardanelles Strait.

This was important as the Dardanelles was the gateway to Constantinople (now Istanbul) and would have meant the toppling of the Ottoman government should this plan be successful.

In that event, the British would also be able to use bases in Turkey and in the Balkans to open up a new front in the Southeast against the Germans.

This would not only have forced the Germans to divide their forces which would have taken much-needed resources and troops from the Western Front, but it would have also given the British a direct supply route to aid the faltering Russians.

The plan was approved, and to lead it Sir Ian Hamilton was named to lead the campaign.

Hamilton was an experienced and able strategist, and he and Churchill were confident that their forces could complete the job.

Churchill’s orders were simple: take Constantinople.

The rest he left to the general to decide.

Hamilton’s plan was to land on three points on the Southwestern tip of the Gallipoli peninsula, then secure the beaches, and sweep North against the Ottomans.

When the landings on Gallipoli took place on April 27 however, everything went wrong from the start.

The army’s maps were inaccurate, and intelligence reports of the Ottomans’ strength were also inaccurate.

So as they disembarked, not only were the beaches much narrower than expected, but the Ottomans also fought unexpectedly fiercely.

The British again found themselves locked in a stalemate, rendering the Gallipoli campaign a disaster before it had barely even started.

It was when all seemed lost, that Hamilton devised a new plan and Churchill managed to convince the government not only to continue the war but also send more troops and resources.

Hamilton’s plan was as thus: 20,000 men would land at Sulva Bay, some twenty miles north of Gallipoli.

Sulva was a good place to target; it had a large harbor, and the terrain was low-lying and easy to travel through.

Most importantly, had much fewer defenders than Gallipoli.

An invasion of Sulva would thus force the Ottomans to divide their forces and free up the army in Gallipoli.

This would cause the stalemate to be broken and the fall of Gallipoli.

However, to command the Sulva operation, Hamilton was forced to accept the most senior Englishman available, Lieutenant General Sir Frederick Stopford.

And under him, Major General Frederick Hammersley was given leadership of the Eleventh Division – he was not Hamilton’s first choice either.

Stopford was a military teacher who had never led troops in war and saw artillery bombardment as the only way to win a battle.

He was also in ill health at the time.

Hammersley, on the other hand, had suffered a nervous breakdown the previous year.

Somehow before it had even started, the battle was already shrouded in an ominous cloud.

Hamilton’s style was to tell the commanders about the purpose of the upcoming battle and leave it to them to decide.

Indeed, at one of their first meetings, Stopford requested changes to the landing plans to reduce risk, which Hamilton accepted.

But he still did have one request.

Since the Ottomans would rush in reinforcements as soon as they found out about the landings, Hamilton tasked Stopford to immediately advance and occupy a range of hills called Tekke Tepe before the Ottomans reached them as soon as they landed.

Although the order was simple enough, Hamilton, not wanting to offend, expressed it as pleasantly as he could, and even more crucially, specified no timeframe.

Unsurprisingly, Stopford totally misunderstood, rather than reaching “as soon as possible” the order to him became “advance to the hill if possible”.

And once the order was passed down to Hammersley, it became vaguer still and less urgent.

But he did decline one request from Stopford, a request for more artillery.

Since they would outnumber the Ottomans ten to one at Sulva, there was no need for more artillery to loosen them up as Stopford wanted.

When they landed on August 7th, again things got messy.

Not only had Stopford’s changes to the landing plans messed everything up, but once they landed, the troops began to argue due to uncertainty over their next steps.

What were they to do? Advance? Consolidate?

Hammersley had no clue, and Stopford was on a boat to oversee the landings which prevented messages from reaching him.

And so the day was wasted away with useless arguing.

The next morning Hamilton realized things had gone very wrong.

From a reconnaissance aircraft, he could see the Bay was still undefended and empty – all they had to do was advance.

Yet the soldiers stayed where they were.

So, fearing the worst, Hamilton decided to visit the front himself.

Once there, he found Stopford in a self-congratulatory mood – all 20,000 had gotten ashore.

At the same time, believing he did not have enough artillery, he was also afraid of an Ottoman counterattack.

So he told Hamilton he needed the day to consolidate their positions and supply lines.

Hearing this, Hamilton struggled to restrain his anger.

The Ottoman reinforcements, you see, had been sighted an hour earlier rushing towards Sulva.

They needed to move that very evening – but Stopford disagreed, it was too dangerous, he said.

Hamilton retained his cool and instead went to visit Hammersley at Sulva.

But to his dismay, he found the soldiers lounging about on the beach as if on holiday.

And Hammersley himself was on the other side of the beach busily supervising the building of his new temporary headquarters.

Asked why he had not moved yet and secured the hills, Hammersley replied that he had sent some brigades under his colonels for that purpose, but once they encountered Ottoman artillery, they were unable to move further without more instructions.

With communications to Stopford taking forever, the operation started to lose its momentum.

And when Stopford was finally reached, Hammersley continued, he had been told to proceed cautiously, rest the men, and advance the next day.

Hamilton could not control himself any longer – a mere handful of Ottomans with a few guns were holding up an army of 20,000 from marching a distance of just four miles!

Although it was night, Hamilton ordered Hammersley to send a brigade to Tekke Tepe – it would have to be a race to the finish.

The next morning, Hamilton would hold his binoculars to his eyes, and to his horror he would see his army in full retreat – the Ottomans had gotten to the hills just thirty minutes before them.

And soon after, the Ottomans slowly began to retake Sulva and eventually pinned the British on the beach.

Some four months later, the British would be abandoning Gallipoli with their tails between their legs and making their way home.

Analysis

In planning the invasion at Sulva, Hamilton had done a marvelous job.

He had taken care of the logistics, he understood the need for surprise, and had located a key point, Tekke Tepe, from which to break the stalemate at Gallipoli.

To get there he crafted an excellent strategy that involved deceiving the Ottomans about where they would land, and how to get there safely, and he even had prepared for any unexpected contingencies.

But he had ignored one thing: the chain of command and communication circuits which would allow him to take control of the situation and enact his strategy.

The first links in the chain of command, Stopford and Hammersley, were both averse to risk, and Hamilton failed to adapt to their weaknesses.

So when he gave his orders in a polite and forceful manner, they simply interpreted the order according to their fears.

Rather than advancing to Tekke Tepe, they understood it as just a possible goal should everything else go well.

The next links were the colonels under Hammersley.

They had no communication with either Hamilton or Stopford, and Hammersley was too terrified to lead them.

Nor did they have the courage to act themselves, lest they ruin a plan they never understood to begin with.

And below them were the soldiers, who, without any direction from their superiors, were left to mill around the beach like lost ants.

Confusion and lethargy then set in, the chain of command was broken, and Gallipoli was lost.

When a failure like this happens, it is natural to look for the cause.

Perhaps it’s the maps, or the officers, or the terrain, or whatever.

But to do that is only to ensure more failure in the future.

The truth is it all starts from the top.

Failure or success is determined by your style of leadership and the chain of command you design.

If orders are vague and half-hearted, by the time they travel down the chain of command and reach the subordinates, they will have become meaningless.

Let people work unsupervised and they will revert to their natural selfishness – they will interpret the orders as they wish and promote their own interests.

Success is determined based on an effective chain of command where orders are relayed quickly, and information reaches back to you just as speedily.

But when the style of leadership is not adapted to the weakest in the group you lead, then the chain of command will certainly break down.

After all, a chain is only as strong as its weakest link.

Control from Afar

In the 1930s, U.S. Brigadier General George C. Marshall was preaching for major military reform.

He argued there were too few soldiers, and that the ones they did have were badly trained.

Additionally, he highlighted that current military doctrine was ill-suited to modern technology, and more.

It turned out that President Franklin D. Roosevelt, in 1939, was readying himself to appoint a new Army Chief of Staff.

WWII was kicking off in Europe, and the President was certain the US was going to get involved at some point.

Roosevelt also understood the need for reform, so he bypassed generals with greater seniority and experience when he chose Marshall for the job.

However, at first, the job seemed a curse in disguise – the War Department was in awful shape.

In the War Department, there were generals who had the power to impose doing things the way they wished it to be done and who had huge egos to boot.

And once a senior officer would complete his service in the military, he would, instead of retiring, take a job in the War Department.

Such officers would then create their own fiefdoms and amassed power which they strove to protect.

A breakdown of communication was frequent, there were overlapping jobs, and the department was a hotbed of inefficiency.

What could Marshall do?

Some ten years earlier, Marshall had served as the assistant commander of the Infantry School at Fort Benning.

And while there, he kept a notebook of the names of promising young men who he thought had potential.

Once he took over the War Department, one of the first things he did was retire the elderly officers and bring in these fresh youngsters.

These officers had initiative and shared the determination and desire necessary for the reform he wanted.

These men would include the likes of Omar Bradley and Mark Clark.

But none was more important than the protégé he spent the most time on: Dwight D. Eisenhower.

It was after the attack on Pearl Harbour that their relationship began in earnest.

Then a colonel, Eisenhower was asked to prepare a report on the attack, and on what could be done in the Far East.

The report showed that Eisenhower shared Marshall’s ideas on how to run the war.

So over the next few months, Marshall would keep Eisenhower in the War Department, they would meet every day, and Eisenhower would use that opportunity to soak up as much knowledge about Marshall’s way of doing things as he possibly could.

As they worked together, Eisenhower’s stock grew in Marshall’s eyes especially when he displayed his patience by not complaining despite desperately wanting to join the field.

And like Marshall, he possessed the quality of getting along with his fellow officers well yet was quietly forceful.

In July 1942, Marshall surprised everyone by naming Eisenhower commander of the European Theatre of Operations.

By this time, he was already a Lieutenant General but was still relatively unknown.

But in the first few months of the job, as the Americans fared poorly in North Africa, the British clamored for a replacement.

However, Marshall would stick with his man and offer encouragement and advice.

One such advice was that he take on a kind of roving deputy who thought the way he did and would act as a go-between between him and his subordinates.

Marshall recommended a man he knew well, Major General Omar Bradley, whose appointment Eisenhower accepted.

With this appointment, the staff structure of the War Department under Marshall was replicated under Eisenhower, and with Bradley in place, Marshall left Eisenhower alone.

Marshall would continue to place his protégés throughout the War Department, and they would quietly spread his way of doing things.

Waste was cut ruthlessly – the number of deputies who reported to him was reduced from sixty to six.

His reports to Roosevelt were also famous for his ability to explain complex subjects in just a few pages.

Marshall disliked excess, when his deputies gave a report that could be given in fewer words, they found that he quickly got bored and that he was not afraid to show it.

In the beginning, he would sit with rapt attention, but when it got too long or wandered, his face would register that he had lost interest.

It was an expression they came to dread, and over time, they began to streamline their communication style and increase their efficiency.

With this, the flow of information up and down the chain of command was increased many times over.

Marshall never yelled nor confronted directly, rather he had a way of communicating his desires indirectly.

This skill would make his staff actually think about what he meant, which allowed them to understand the spirit of his orders.

Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves, military director of the project to develop the atomic bomb, once came to his office in order to get him to sign off on $100 million in expenditures.

But Marshall was not aware of his presence and carried on diligently focusing on the matter at hand.

When his attention finally turned to Groves, he took the request, signed it, and said, “It may interest you to know what I was doing: I was writing a check for $3.52 for grass seed for my lawn.”

The thousands who worked under Marshall, whether at home or abroad, did not need to see him to feel his influence.

They felt it in the short but insightful reports he wrote, the speed of his responses, and the efficiency of his department.

Yet, when he transformed the US Army and War Department in a few short years, few at the time understood how he did it.

Analysis

When he first became Army Chief of Staff, he knew he would have to hold himself back.

He would not be able to fight everyone and everything, be it egotistical generals, careless waste, or the political feuds in the department.

No, he was too smart to do that – there were just too many fights that would lead to exhaustion and, in the end, stroke.

And should he micromanage everything, he would become embroiled in unnecessary arguments which would make him lose sight of the bigger picture.

The only way was to step back and control others indirectly.

In fact, he ended up doing so with such a light touch, that nobody really knew how thoroughly he really dominated.

The key to Marshall’s strategy was the grooming and placement of protégés.

He turned them into competent deputies who shared his beliefs, and could enact the spirit of his orders, yet were able to think for themselves.

By doing this he was seen as a delegator rather than a manipulator.

And although his cutting of waste was heavy-handed at first, when his stamp of efficiency was firmly placed on the department, there were fewer useless reports to read and less time wasted at every level.

The political types were forced either to join in this spirit or simply leave.

His indirect approach amused many especially when they found him fussing over even a garden bill.

But they would soon realize that should they waste even a single penny; their boss would know.

Just like the War Department back then, today’s world is also complex and chaotic.

Should you try to control everything, you’ll be seen as a dictator, however letting everything go will also lead to confusion and chaos.

The solution is to do what Marshall did: find deputies who think for themselves yet will act as you would in their place, cut down on waste streamline the organization, and develop the spirit of camaraderie.

Once that is done, the organization becomes essentially self-policing, and when time is not wasted on petty details, you will be able to have a fuller look at the bigger picture.

For people to follow without feeling bullied, that is the ultimate in control.

The Way of Leadership

More so now than ever before, leadership requires a deft touch.

Not only have we become more distrustful of authority, but we also all see ourselves as authorities in our own right.

So, feeling the need to assert themselves, individuals put their interests first, thus rendering group unity fragile.

This affects leaders in ways they do not even realize.

The tendency today is to give the group more power; leaders let the group make decisions, polls are conducted for opinions, and subordinates are given the opportunity to craft overall strategy.

By desperately wanting to seem democratic, they let the politics of the day seduce them into losing the unity of command.

This happens to be the same thing that has caused some of the greatest military defeats in history.

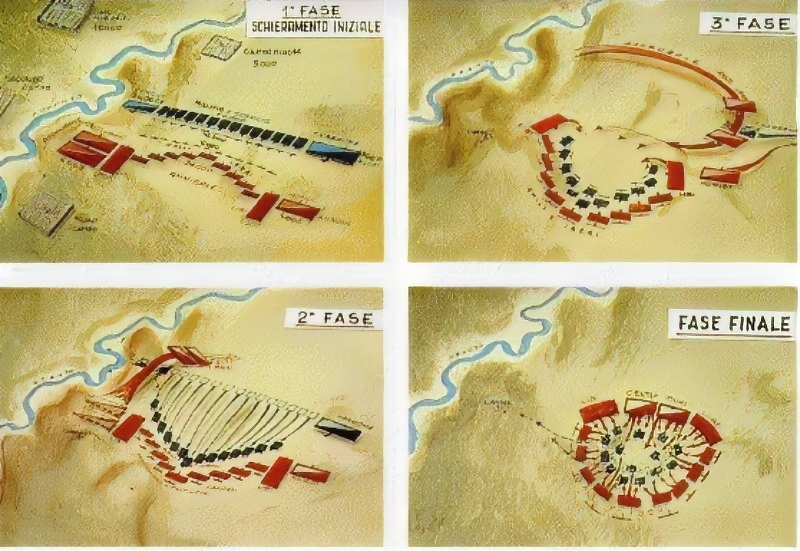

And perhaps the foremost of these defeats was the Battle of Cannae (216 B.C.) where the Carthaginian General Hannibal defeated a Roman army twice the size of his own.

And yes, while Hannibal was a military genius and much can be said about the strategic masterclass he put on during this battle, much of the cause, or blame rather, for his victory was down to the Romans themselves.

They had sacrificed their unity of command when they appointed two men to lead the army instead of one.

Hence, was it such a surprise that those same two men fought with each other as much as they fought the Carthaginians?

This sort of victory was again replicated by Frederick the Great during the Seven Years’ War when he defeated five Great Powers who were allied against him.

This was certainly due to being able to move and issue orders faster than his enemies who had to consult with each other over every issue.

This is why Marshall, who was painfully aware of the pitfalls of having many leaders, argued during WWII that there should just be one supreme commander who should lead the Allied armies.

But it seems the Americans forgot this principle in the Vietnam War, during which North Vietnamese General Vo Nguyen Giap enjoyed a huge advantage due to his unity of command in contrast to the Americans whose strategies were crafted by a crowd of politicians.

The Pitfalls of Groupthink

Divided leadership is fatal in groups as groups often think in ways that are illogical and ineffective – and this is exactly what groupthink is.

The reason for this is because groups are political.

Where an individual can look at things dispassionately, and come up with bold and creative solutions quickly, in a group each member tries to improve their own image within that group, which ends up meaning that each decision must satisfy everyone’s ego.

The result is that groups are cautious, slow-moving, slow to decide, unimaginative, and sometimes purely irrational.

So here is what must be done.

Do whatever you can to preserve the unity of command.

Keep the strings of control in your hands, and let the overall strategic vision come from you alone.

Yet, work behind the scenes, and make it seem everyone is involved in your decisions.

Consult for advice; take the good, deflect the bad.

If necessary, make a few cosmetic changes to the strategy to assuage the political beasts in the groups, but ultimately, trust your own vision.

But remember the first rule: never relinquish unity of command.

Rule through Delegation

Control is very elusive and needs subtlety.

Often the louder you shout and the harder you tug; the more people will resent and try to resist.

Early in his career, the legendary filmmaker Ingmar Bergman would be filled with frustration due to how taxing the implementation of his vision as a director was.

And due to this pressure, he would lash out at his cast and crew, who would stew with resentment over his dictatorial ways.

To make things worse he would change his cast and crew with every film which only put him back to square one every time.

Eventually, he understood his mistake and assembled a talented crew of cinematographers, art directors, and actors whom he trusted from across Sweden.

They would allow him to loosen his grip on the reins of power and allow him to gain greater control as a result.

Assembling a skilled team is an effective way of creating an efficient chain of control.

By doing so you have motivated, spirited people working under you.

They allow you to delegate and to be seen as democratic, and help you save valuable time and energy which is instead allocated to focusing on the bigger picture.

In creating such a team, you look for people who make up for your deficiencies.

Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War had a strategy, yet his generals disdained him for his lack of military experience.

And what good was a strategy that couldn’t be executed?

But when he found in Ulysses S. Grant, a man who shared his belief in offensive warfare, and who did not have an oversized ego, he partnered with him and put him in command to run the war as he saw fit.

Yet, be careful not to be seduced by a glittering resume.

A good character, the ability to work as part of a team and also independently, and the ability to take responsibility are equally key.

Even if you are strapped for time, look past the flashiness, and instead look at his psychology and character.

This is exactly why Marshall tested Eisenhower for so long.

Rely on Yourself

And even though you can rely on your team, do not be its prisoner.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt had his infamous “brain trust”, a group of advisors and cabinet members who he consulted for opinions and ideas.

But never let them into his actual decision-making.

He saw them simply as tools and didn’t let them build up power within the administration.

He understood the need for unity of command but was never seduced into violating it.

The “Directed Telescope”

Another matter you must consider is that as the flow of information travels down the chain of command, it often gets diluted along the way and loses its urgency.

To combat this, make sure your orders are clear and concise.

And make a habit of visiting the frontlines incognito to see how your orders and reforms are taking effect.

This was something Marshall did to great effect within the War Department.

Then there is the concept of the “directed telescope” which the author Martin van Creveld talks about concerning Napoleon.

This was a brigade of officers chosen for their intelligence and loyalty, who were sent to get information on any part of the army by acting as a “directed telescope” in order to get the sort of information he could not get about how things were going through normal channels.

By cultivating these sorts of individuals and placing them throughout the group, you give flexibility in the chain and give yourself room to maneuver in a generally rigid environment.

Political Beasts

The greatest problem in your chain of command is often those political beasts.

Such people are inescapable – they try to build factions to further their own agendas and fracture the cohesion you have built.

But there are a few things that can be done to weed them out before they arrive.

Aim to see if a potential hire is restless and moves around a lot.

This is a sign of the sort of ambition which prevents them from fitting in.

And when people share your ideas, be wary, as they may just be mirroring you to charm you simply to get into your good graces.

The court of Queen Elizabeth I was full of such types.

So she made it a habit never to divulge her opinions.

That way, no one, not even those in her inner circle knew where she stood which meant they could not disguise their intentions behind a façade of perfect agreement.

Another method is to isolate such people.

Marshall did this when he infused his spirit of efficiency within the group.

Those who tried to resist were easily identified and were ostracized for ruining the team spirit.

This gave them no room to maneuver.

In any case, be careful not to be naïve.

Act fast so these types cannot grow a power base with which they will destroy your authority.

Inspiring Orders

Finally, the ability to give orders is itself an art that must be cultivated as well.

Orders must not be vague, for then they will be hopelessly altered and reinterpreted.

Yet you do not want to be too specific or narrow as that will encourage people not to think for themselves.

It must be clear yet allow for enough leeway for the subordinate to inject their own creativity in how it is executed.

When it comes to this Napoleon was a master.

His orders were full of details which gave his subordinates a look into how his mind worked, whilst giving them interpretative leeway.

He would spell out possible contingencies, suggesting how the officer could adapt the command if necessary.

But his directives were also inspiring.

Rather than making the officers feel like the minions of some distant emperor, his orders would empower them and make them feel a part of a greater cause.

Here is an example of an order he gave:

“Tomorrow at dawn you depart [from St. Cloud] and travel to Worms, cross the Rhine there, and make sure that all preparations for the crossing of the river by my guard are being made there. You will then proceed to Kassel and make sure that the place is being put in a state of defense and provisioned. Taking due security precautions, you will visit the fortress of Hanau. Can it be secured by a coup de main? If necessary, you will visit the citadel of Marburg too. You will then travel on to Kassel and report to me by way of my charge d’affaires at that place, making sure that he is in fact there. The voyage from Frankfurt to Kassel is not to take place by night, for you are to observe anything that might interest me. From Kassel, you are to travel, also by day, by the shortest way to Koln. The land between Wesel, Mainz, Kassel, and Koln is to be reconnoitered. What roads and good communications exist there? Gather information about communications between Kassel and Paderborn. What is the significance of Kassel? Is the place armed and capable of resistance? Evaluate the forces of the Prince Elector in regard to their present state, their artillery, militia, and strong places. From Koln you will travel to meet me at Mainz; you are to keep to the right bank on the Rhine and submit a short appreciation of the country around Dusseldorf, Wesel, and Kassel. I shall be at Mainz on the 29th in order to receive your report. You can see for yourself how important it is for the beginning of the campaign and its progress that you should have the country well imprinted on your memory.”

A Directive by Napoleon Sent to a Field General Under Him

Wrapping Up

Simply put, there is no good to divided leadership.

Should you be offered a shared position, turn it down.

Otherwise, when that enterprise fails – and it will indeed fail – you will be blamed for it.

However, it is also wise to take advantage of your opponent’s faulty command structure.

If your opponent is ruled by a committee or it has a shared leadership, never fear them – your advantage is already great.

In fact, do as Napoleon did and seek out such opponents.

With such opponents, you would be a fool to lose.

Footnotes & Further Reading

Greene, Robert. The 33 Strategies of War. Millionaire