Looking back, it is safe to say that the ten or so years before 1792 gave little sign as to the avalanche of changes that were soon going to shock Europe.

Soon, Europe would be engulfed in the French Revolutionary Wars, and then the Napoleonic Wars.

Yet, after the American Revolutionary War (1775-83) had pitted Britain against France, Spain, the Netherlands, and the American revolutionaries, the general climate in Europe had become more subdued.

That is not to say, however, that the occasion regional conflict did not occur during this period.

Indeed, while the eastern monarchies of Russia, Prussia, and Austria concerned themselves with the futures of Poland and the Ottomans, Britain and France continued their traditional maneuvering over the Low Countries.

Still, these tussles were mainly regional rather than being reminiscent of the wider continental conflicts that would come later.

Calm Before the Storm

After 1783, Britain and France’s conflict became more focused on a rivalry over maritime trade and commercial activities.

But their mutual suspicions of one another would show when in 1787-8 the pro-French government in the Netherlands was forced out by Prussian troops backed by the unwavering support of British Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger.

Yet, Pitt’s more active diplomacy was not only due to his personality.

The British had made a great recovery since they lost the Thirteen Colonies in 1783.

In addition to the boosting of their economy and the expansion of transatlantic trade during this time, the Industrial Revolution was also well underway, the Royal Navy was well administered and funded, and Pitt’s fiscal reforms had laid solid foundations to support any future British maneuvering abroad.

Granted, that did not mean political leaders in London were expecting another Great Power war in the foreseeable future.

And the biggest reason for this was the worsening condition of France during this period.

French Difficulties

For a few years after their victory in the American Revolutionary War, the French seemed as strong as ever – the domestic economy was doing well, and its foreign trade with its colonies was rapidly expanding.

Yet the sheer cost of that war, totaling more than its previous three wars put together, coincided with a failure to reform the national finance system, which in turn interacted with a growing discontentment with the ancien régime.

From 1787, the internal crisis worsened and began affecting its role play in foreign affairs.

Its diplomatic defeat in the Netherlands, for example, came as part of a recognition that they could not finance another conflict with both Britain and Prussia.

And when in 1790 an Anglo-Spain clash over Nootka Sound brought the two to the brink of war, Spain begrudgingly had to withdraw due to the French Assembly challenging Louis XVI’s right to declare war.

None of this, though, would suggest that France would be soon looking to upend the entire ‘old order’ of Europe.

The road to the conflict that would consume the entirety of Europe over the next two decades (*cough* Napoleonic Wars) thus began quite unevenly.

The Bastille Falls

The French, for one, were too concerned with domestic matters, especially after the fall of the Bastille which signalled the start of the French Revolution.

And although the increasing radicalization of French politics worried some governments, the turmoil in Paris and the surrounding French provinces meant France was of little account in the wider continental maneuverings.

In fact, it was for that reason that Pitt was considering a winding down of British military expenditure, while the eastern monarchies continued concentrating on carving up Poland.

On the War Path

It was only when the first émigré plots to restore the monarchy were discovered, and also after the revolutionaries shifted towards a more aggressive foreign policy that an escalation towards war occurred.

Yet the Allied armies were clearly ill-prepared for any war that was to take place against France, as demonstrated by their subsequent defeat at Valmy (1792).

It was only when French successes started threatening the Low Countries, the Rhineland, and Italy did the rest of Europe start wake up to the new reality.

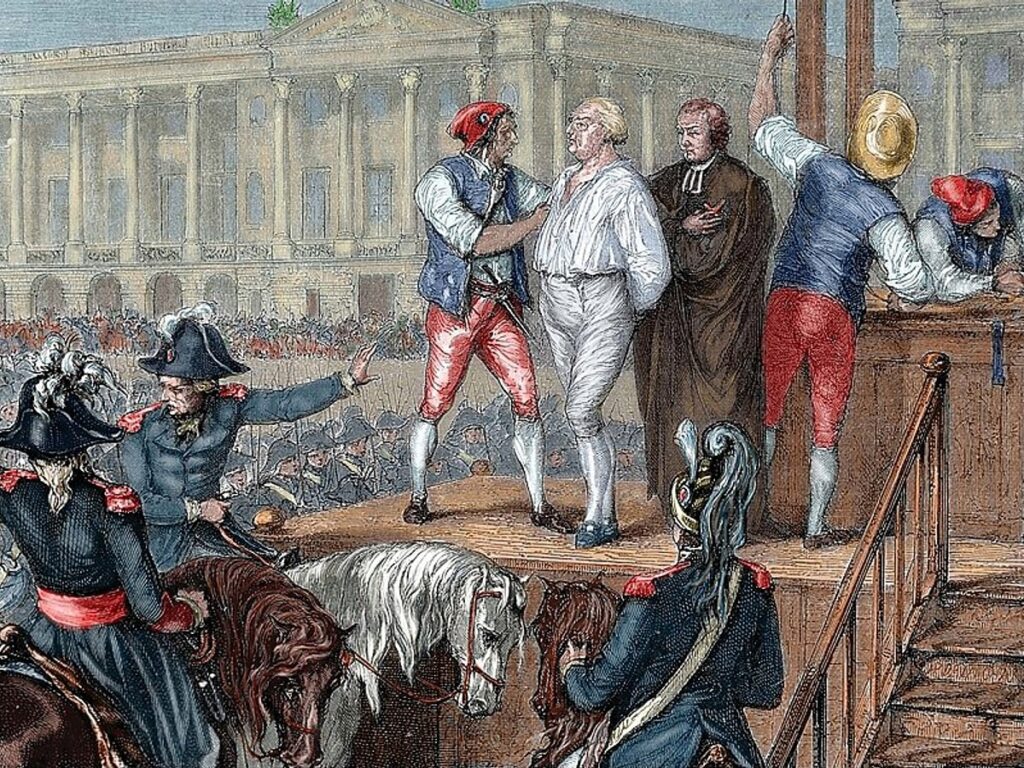

And it was with the execution of Louis XVI that other monarchs truly began to understand the grave consequences that would occur should this radical ideology be allowed to expand past France’s borders.

Just like that, the ensuing French Revolutionary Wars took up its full strategic and ideological dimensions.

War of the First Coalition

The original combatants, Prussia and Austria, were now joined by all of France’s neighbors, along with Britain and Russia.

However, this First Coalition was doomed to fail.

It may have been hard to see why the First Coalition failed at the time, especially considering the overwhelming odds against the French.

However, in hindsight, there were important indicators pointing to a French victory.

First was the sheer desperation of the revolutionaries which forced them to use any and all sizable French resources for the purpose of fighting their foes.

And it has also been pointed out that a very important period of reform had occurred within the French Army.

The Revolution, you see, had gotten rid of the aristocratic hindrances which prevented reformers in the army from trying new methods of battle and organization.

Thus, the ‘total war’ methods and innovative tactics deployed on the battlefields of the upcoming conflict were as much a reflection of the spirit of the Revolution as it was of the cautious, half-hearted fighting of the Coalition.

So now, with an army of 650,000 by 1793, sky-high morale, and a willingness to take risks with aggressive tactics and lengthy marches, the French soon began overrunning their neighbors’ territories.

And what this meant was that the cost of maintaining such a huge army fell upon not the French economy, but on those now-occupied regions outside of France.

Any power now attempting to blunt their ferocious expansion would now need to also find a way to deal with this new way of fighting.

Interestingly, this task was not as impossible as it seemed.

The French army during the early years of the revolution and later under Napoleon had deficiencies in organization and training, along with weaknesses in supply and communications which a well-trained foe could exploit.

But where was that well-trained opponent?

Problems of the First Coalition

The coalition members had generals who were comparatively elderly, and armies which were slow-moving and less tactically adept than the innovative French.

And another problem was the intoxicating ideals of the revolution which seemed attractive not only to French soldiers and citizens but also those of the neighbouring territories.

This question of morale was only solved later when Napoleon turned ‘liberation’ into conquest and plunder, which opposing nations could point to in order to inject patriotism and a hatred of Napoleon into their soldiers.

Apart from this, the coalition failed due to a lack of unity.

At this point, the only thing that unified the coalition was the promise of British subsidies and not much else.

After all, the revolutionary war overlapped with the demise of Poland which meant the eastern monarchies could only turn part of their attention to France.

Whenever Russia aimed to reduce Polish independence further, this only made the Prussians and Austrians feel the need to reinforce their eastern flank at the expense of the Western campaign against France.

So by the time the third and final partition of Poland occurred in 1795, it was only too clear that Poland was an effective ally to the French in its death-throes than as a living, functioning state.

Indeed, the Polish affair had diverted too much of Prussia’s resources eastwards, which meant that when the French came knocking they were forced to sue for peace and agree to an uneasy neutrality, as did the rest of the smaller German states.

And by then, the Netherlands had been overrun, and Spain had been forced to abandon the Coalition and create an anti-British alliance with France instead.

Then there were just three: Sardinia-Piedmont, Austria, and Britain.

In early 1797, Sardinia-Piedmont was crushed by Napoleon; as for the unfortunate Austrians, they were driven out of most of Italy and forced into the Peace of Campo Formio (1797).

In Britain, despite the younger Pitt hoping to emulate his father in checking the French, there was a broad failure to conduct the war with an appropriate level of strategic clarity and determination.

Strategical Misgivings of the British

An expeditionary force under the Duke of York was sent to the Low Countries in 1793-5 but was simply no match for the French, and had to return home with their tails between their legs.

Moreover, there was general aversion on the part of the British ministers to any large-scale continental operation, rather they preferred utilizing the Royal Navy to conduct a maritime blockade and raids up and down the enemy coast.

Especially considering the Royal Navy’s superiority over its French counterpart, this seemed like an easy and attractive option.

Soon, however, they would pay dearly for this strategical diversion from continental warfare – in 1793-6, a disease contracted during their operations near the West Indies resulted in the deaths of 40,000 and another 40,000 being rendered unfit for service.

Not only did these unnecessary operations fail to help lighten the war’s load on the treasury, it is doubtful the Royal Navy even did much to blunt France’s growing power.

So when the subsidies being sent to the other allies simply became too much for even Britain to pay, it became clear that Britain’s strategy was not only inefficient, it was expensive.

And by the time Pitt realized this, the War of the First Coalition (1792-1797) had already been lost for its allies in Europe.

Locked in Stalemate

In much the same way Britain realized it could not beat France on land, the revolutionary government also realized it could not beat Britain on sea.

This was made very clear when it tried to invade Ireland early on during the conflict.

And when the Spanish and Dutch joined the war on the French side, they also saw their fleets destroyed by the British.

This would also lead to the British progressively taking their colonies, which provided new markets for British goods.

Herein lay the strategic dilemma which would plague the two for the next two decades.

Like the whale and the elephant, each was strongest and largest in its own domain.

But British control of the sea routes could not by itself defeat the French on land.

And as for the French, as long as Britain was alive and offering subsidies to anyone who suffered as a result of French expansionism, it could never be too sure the continental powers would continue to accept French suzerainty.

That was why Napoleon argued in 1797 that they should be concentrating on building their fleets to destroy Britain.

So as long as one was master of land and the other of sea, each would continue to look for the winning card to tilt the balance in their favour.

When Napoleon finally did attempt to alter the balance in the summer of 1798, it was characteristically risky… and bold.

War of the Second Coalition

He would land in Egypt with 31,000 troops and quickly placed himself in a commanding position to dominate the Middle East, the Ottoman Empire, and the route to India.

Britain was at the time in a shaky position and was distracted with other commitments, namely by yet another French expedition to Ireland (to serve as a distraction of course).

Truly it was a masterful move – had the French succeeded it would have dealt a dreadful blow to the British.

But just as Paris suspected, Napoleon’s subsequent setbacks in Egypt would lead all those nations who resented French predominance to abandon their neutrality and join the War of the Second Coalition (1798-1802).

And this time, Portugal, Naples, Austria, Russia, and the Ottomans were all in the war, and all queued to receive British subsidies.

Now with Napoleon tied and unable to win in the Middle East, and after France’s loss in Italy and Switzerland, things were really starting to look bleak for the revolutionaries.

Yet, like the First Coalition, the Second Coalition rested on shaky political and strategic foundations.

Off to a Rocky Start

Not only was a Northern Front unable to be opened due to Prussia’s absence, but the King of Naples’ premature campaign ended in disaster, whilst an Anglo-Russian army failed even to rouse the local population against the French when it arrived in Holland, thus forcing it to retire.

And you would also be sorely mistaken for thinking Britain would learn its lesson from the previous campaign.

Rather than expanding their continental operations, they sat contentedly in the ocean despite it serving no real strategic objective.

Even worse, after the failed Austro-Russian defense of Switzerland, Russia was driven back through the mountains by the French.

By now deeply resentful of British policy, the czar showed a willingness to negotiate with Napoleon (who by now had slipped back into France) and soon withdrew from the war.

Austria, now left alone to face the brunt of France’s fury, sued for peace after being smacked about by the French three times in the space of just eighteen months.

From Bad to Worse

From then on, a situation that already seemed bad would take a turn for the worse for the Second Coalition.

Prussia and Denmark, who were not a part of the war, opportunistically chose that very moment to overrun Hanover, whilst Spain decided to launch an invasion of Portugal.

So by 1801, Britain was left to stand alone, as it had done three years earlier.

And to rub in the salt, the League of Armed Neutrality was rehabilitated (it was first used during the American Revolutionary War) by Russia, Denmark, Sweden, and Prussia.

That being said, away from Europe, Britain once again did rather well.

Not only did it seize Malta from the British, thus gaining a great military base for the Royal Navy, the French were also expelled from Egypt after a defeat at Alexandria (Napoleon was long gone by then).

Further afield, the French were defeated in India, and various French, Dutch, Swedish, and Danish possessions were seized in the West Indies.

As for the ill-fated League of Armed Neutrality, it didn’t last long after a Danish fleet was smashed off the coast of Copenhagen in 1801.

French Revolutionary Wars End; Preparations Begin for the Napoleonic Wars

Nevertheless, the inconclusive battling with France led the British politicians to think of peace, especially with its merchants complaining about the damage the war was doing to its commerce.

And in Napoleon’s calculation, there was little to be lost from a period of peace.

It would give a chance for French influence in its satellite states to be consolidated, whilst British diplomatic influence would certainly be barred.

Additionally, the peace would give its navy the chance to be rebuilt, and meanwhile economy would be rested in anticipation of the next round of the struggle.

But after the Peace of Amiens (1802), British opinion would steadily sway towards the reopening of the conflict, especially with the French continuing the struggle in other ways.

Not only was British trade denied entry into much of Europe, but London was prevented from meddling in Dutch, Swiss, and Italian affairs.

And all across Europe and in the colonies, French intrigues and aggressions were reported, along with evidence of a large-scale French warship-building program.

On the back of these events, a temporarily cold war quickly escalated into a hot one, thus kicking off the Napoleonic Wars in 1803.

Footnotes & Further Reading

Kennedy, Paul M. The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500-2000. London: William Collins, 2017.